FADING GLORY: JARAL DE BERRIO

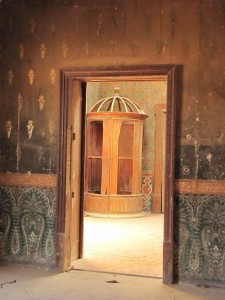

Collapsing walls, ceilings and floors, torn and scratched 19th century French wallpaper and frescoes, broken marble friezes and floral moldings, sagging silk that once adorned surfaces, Jaral de Berrio remains but a relic of its former glory. Purported to have been the largest and most grandiose haciendas in Mexico, it stands quietly abandoned.

This “Versailles” hacienda, built in the 1770’s in the state of Guanajuato, is fading fast. Photographs taken over the past few decades testify to this. Some predict that one day, not so far into the future, all that may remain is a vast stone, plaster, wood and tile shell. Already a few sections of its roof invite one to gaze at the blue sky — or avoid the rain. Walking along its floors can pose a hazard. Just recently, to prevent further vandalizing, it was closed to the public. Sadly, there’s really not much left to vandalize…

According to the Mexican/American author, Luis Alberto Urrea, the word Jaral relates to a typical Mexican and Southwest desert vegetation. Berrio is the Marquis’ family name. Legend has it that the their property once extended from Durango, Texas to Mexico City. In the 1830’s, one of the descendants was purported to be the wealthiest man in what had recently been, New Spain. Like many large-scale haciendas it has been in a downhill spiral since the 1910 – 1920 Mexican Revolution.

The Revolution’s social and land-use reformations leading to the dismantling of the elite ruling class properties would by no means spare this one. “The radical and egalitarian sentiments produced by the Revolution had made landlord rule of the old kind impossible.” (Wikipedia). Ejidos, or communally owned agrarian properties before the Spanish conquest, were re-introduced—albeit on a small scale.

Even before the tumultuous days of the Revolution, the complexities of running such a mega hacienda that could house a very large crowd while alongside cattle, produced gunpowder and mescal, was no small matter. “Skillful family tactics and a deft role in the often brutal world of Mexican rural politics held the domain together and, by 1890, Juan Isidro Moncada y Berrio had inherited what had become a marquis´s mansion,” wrote Timothy Brittain-Catlin in the 1970’s.

Once housing 6400 of which 1700 were servants and workers —or so the legend has it, only a watchman and groundskeeper remain today. The owner is an architect in Mexico City. Restoration would be a long shot. The remaining challenge is to keep at bay miscreants intent on looting it.

Catching my eye as a testament to the former unabashed wealth of its owners or hacenderos, is the sad sight of torn and drooping silk that once embellished its ceilings. Metal, cage-like frames offer a hint of crystal chandeliers while a dancing nymph fresco suggests that this may have been the master bedroom.

Today, instead of the Marquis’ family’s entourage of friends, dignitaries and extensive family — one of the ancestors was said to have 99 children — swallows, doves and bats call it their home.

Last March, on a royal blue sky spring day, I was given the opportunity to explore this 300 year old palace with Jo Brenzo, a photographer and gallery owner in San Miguel de Allende.

Driving through the dry, stark, high desert plateau, punctuated by native cacti, yucca, mesquite, and yellow blooming huizache trees, the hacienda, a couple of churches and three immense stone granaries suddenly arose like a mirage before us. More like an architectural oasis. Gone is the family’s former railroad station, post office, gunpowder factory, and two schools. A pueblo must be nearby but I didn’t see it.

We parked on a dusty “plaza” where only a campesino driving a burro on his old wooden wagon passed us by. Behind him was a wall with a faded Coca Cola ad.

Getting a sense of the remaining enclave here I had a double take. What a curious juxtaposition of structures! Would any film set designer ever conceive of such a landscape where an ornate church facade is rubbing elbows — actually competing in size — with three granaries the shape of dunce caps?

As we approached the hacienda’s rather unwelcoming large wooden door, I looked up to “Medievalesque” polygonal turrets piercing the sky while attempting to make sense of the architecture. Here was a fantastical blend of the Moorish, Classical, and Baroque Not surprisingly, looming from above was the statue of the Berrio marquis perched on an ornamental pedestal.

As Jo greeted the caretaker, someone said: “The colors remind me of Petra.” Having never been there India’s Fathepur Sikri came to mind. A sandstone palace with a mosque, it had also turned into a ghost town. The engineers and architects had not predicted a paucity of water. And so they went on to build Shah Jahan’s jewel: the Taj Mahal, just down the road.

Today, upon entering Jaral de Berrio’s main courtyard — one of many in this multi-roomed complex, I was a tad disappointed. Here was a typical but rather plain fountain on barren ground with little vegetation to soften the edges. Something unusual stood out though. Under the golden Moorish porticos were rows upon rows of perfectly stacked wooden barrels. [Mescal barrels] Containing mescal distilled and bottled here, I later discovered it being sold in a dusty, poorly lit room by the entrance. Soon I began to encounter its handsomely labeled bottles in both San Miguel de Allende and Mexico City.

Walking up the grandiose oval staircase surrounded by pale faux marble walls we noticed the painted ceiling depicting a Fragonard-like blue sky and clouds.

Continuing along a never-ending balustrade facing the courtyard my curiosity was piqued as I looked more closely at a delicate border of small frescoes. [Mythical creature] Depicted here was an unusual, mythical creature sporting large fangs — a monster I would not wish to encounter in my dreams…

We began eagerly to explore and photograph room after room after room — each bearing its own particular stamp. Floors went from tile to wood and back again; wall surfaces almost flowed as did torn silks, all morphing into new patterns and colors. The sight of decay was riveting while the smell of bat dung in Morrocan-styled room made it too repulsive to loiter.

Having first focused with my camera on the interior rooms with their blend of subtle colors and unusual juxtapositions, both floral and abstract, shadows began to haunt me.

Swallowed up by the vast collection of endless rooms, I headed back out to the fresh air of the inner courtyards. I simply wandered, explored, tripped over rocks and past servants’ quarters suddenly come upon elegant stables. Built solidly of stone, their proportions were exquisite.

Towards the end of the day, Jo Brenzo invited me to “dance” in a white gown while she captured me with her camera. I was transformed into one of the many ghosts that will never disappear even as Jaral de Berrio fades.